- Linux File Permission Tutorial: How to Check and Change Permissions

- How to View Check Permissions in Linux

- Check Permissions using GUI

- Check Permissions in Command-Line with Ls Command

- Using Chmod Command to Change File Permissions

- Define File Permission with Symbolic Mode

- Define File Permission in Octal/Numeric Mode

- Changing User File and Group Ownership

- File permissions and attributes

- Contents

- Viewing permissions

- Examples

- Changing permissions

- Text method

- Text method shortcuts

- Copying permissions

- Numeric method

- Bulk chmod

- Changing ownership

- Access Control Lists

- Umask

- File attributes

- Extended attributes

- User extended attributes

- Preserving extended attributes

- Tips and tricks

- Preserve root

Linux File Permission Tutorial: How to Check and Change Permissions

Home » SysAdmin » Linux File Permission Tutorial: How to Check and Change Permissions

Linux, like other Unix-like operating systems, allows multiple users to work on the same server simultaneously without disrupting each other.

Individuals sharing access to files pose a risk exposing classified information or even data loss if other users access their files or directories. To address this, Unix added the file permission feature to specify how much power each user has over a given file or directory.

In this tutorial, you will learn how to view and change file permissions in Linux.

How to View Check Permissions in Linux

To start with file permissions, you have to find the current Linux permission settings. There are two options to choose from, depending on your personal preference: checking through the graphical interface or using the command.

Check Permissions using GUI

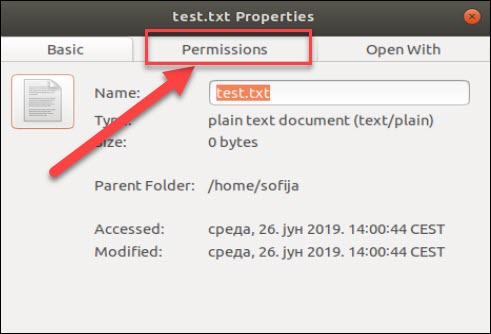

Finding the file (directory) permission via the graphical user interface is simple.

1. Locate the file you want to examine, right-click on the icon, and select Properties.

2. This opens a new window initially showing Basic information about the file.

Navigate to the second tab in the window, labeled Permissions.

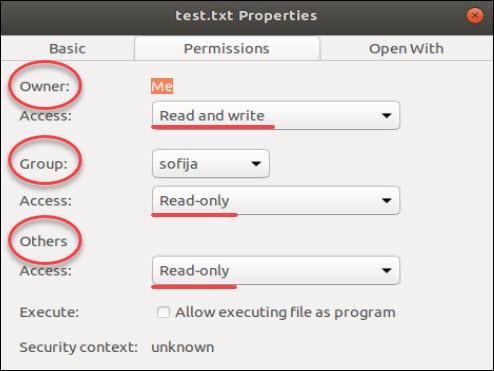

3. There, you’ll see that the permission for each file differs according to three categories:

- Owner (the user who created the file/directory)

- Group (to which the owner belongs to)

- Others (all other users)

For each file, the owner can grant or restrict access to users according to the categories they fall in.

In our example, the owner of the file test.txt has access to “Read and write”, while other members of its group, as well as all other users, have “Read-only” access. Therefore, they can only open the file, but cannot make any modifications.

To alter the file configuration, the user can open the drop-down menu for each category and select the desired permission.

Additionally, you can make the file executable, allowing it to run as a program, by checking the Execute box.

Check Permissions in Command-Line with Ls Command

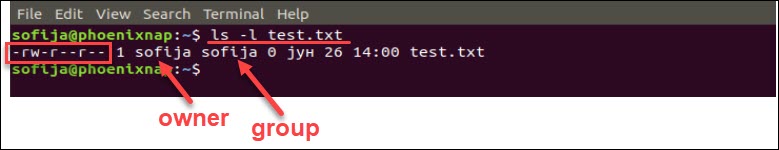

If you prefer using the command line, you can easily find a file’s permission settings with the ls command, used to list information about files/directories. You can also add the –l option to the command to see the information in the long list format.

To check the permission configuration of a file, use the command:

For instance, the command for the previously mentioned file would be:

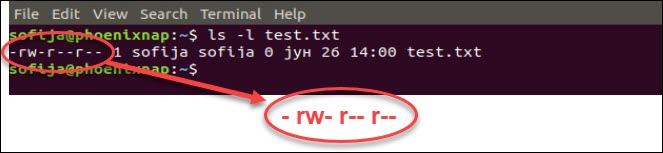

As seen in the image above, the output provides the following information:

- file permission

- the owner (creator) of the file

- the group to which that owner belongs to

- the date of creation.

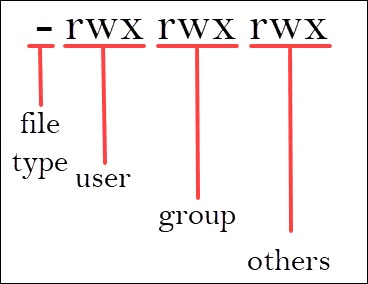

It shows the permission settings, grouped in a string of characters (-, r, w, x) classified into four sections:

- File type. There are three possibilities for the type. It can either be a regular file (–), a directory (d) or a link (i).

- File permission of the user (owner)

- File permission of the owner’s group

- File permission of other users

The characters r, w, and x stand for read, write, and execute.

The categories can have all three privileges, just specific ones, or none at all (represented by –, for denied).

Users that have reading permission can see the content of a file (or files in a directory). However, they cannot modify it (nor add/remove files in a directory). On the other hand, those who have writing privileges can edit (add and remove) files. Finally, being able to execute means the user can run the file. This option is mainly used for running scripts.

In the previous example, the output showed that test.txt is a regular file with read and write permission assigned to the owner, but gives read-only access to the group and others.

Using Chmod Command to Change File Permissions

As all Linux users, you will at some point need to modify the permission settings of a file/directory. The command that executes such tasks is the chmod command.

The basic syntax is:

There are two ways to define permission:

- using symbols (alphanumerical characters)

- using the octal notation method

Define File Permission with Symbolic Mode

To specify permission settings using alphanumerical characters, you’ll need to define accessibility for the user/owner (u), group (g), and others (o).

Type the initial letter for each class, followed by the equal sign (=) and the first letter of the read (r), write (w) and/or execute (x) privileges.

To set a file, so it is public for reading, writing, and executing, the command is:

To set permission as in the previously mentioned test.txt to be:

• read and write for the user

• read for the members of the group

• read for other users

Use the following command:

Note: There is no space between the categories; we only use commas to separate them.

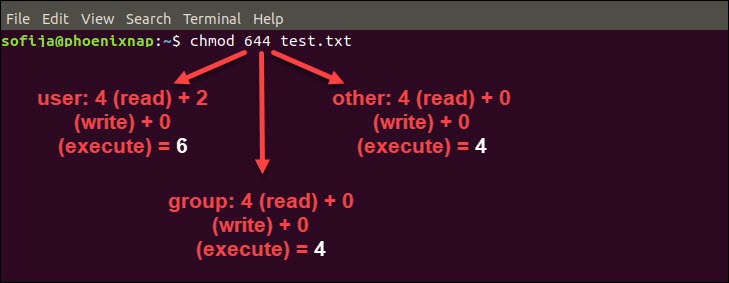

Another way to specify permission is by using the octal/numeric format. This option is faster, as it requires less typing, although it is not as straightforward as the previous method.

Instead of letters, the octal format represents privileges with numbers:

- r(ead) has the value of 4

- w(rite) has the value of 2

- (e)x(ecute) has the value of 1

- no permission has the value of

The privileges are summed up and depicted by one number. Therefore, the possibilities are:

- 7 – for read, write, and execute permission

- 6 – for read and write privileges

- 5 – for read and execute privileges

- 4 – for read privileges

As you have to define permission for each category (user, group, owner), the command will include three (3) numbers (each representing the summation of privileges).

For instance, let’s look at the test.txt file that we symbolically configured with the chmod u=rw,g=r,o=r test.txt command.

The same permission settings can be defined using the octal format with the command:

Define File Permission in Octal/Numeric Mode

Note: If you need a more in-depth guide on how to use Chmod In Linux to change file permissions recursively, read our Chmod Recursive guide.

Changing User File and Group Ownership

Aside from changing file permissions, you may come across a situation that requires changing the user file ownership or even group ownership.

Performing either of these tasks requires you first need to switch to superuser privileges. Use one of the options outlined in the previous passage.

To change the file ownership use the chown command:

Instead of [user_name] type in the name of the user who will be the new owner of the file.

To change the group ownership type in the following command:

Instead of [group_name] type in the name of the group that will be the new owner of the file.

Learning how to check and change permissions of Linux files and directories are basic commands all users should master. To change file’s group permissions, you might find helpful our article on how to use the chgrp command.

No matter whether you prefer using the GUI or command-line, this article should help you better understand how to use file permissions.

File permissions and attributes

File systems use permissions and attributes to regulate the level of interaction that system processes can have with files and directories.

Contents

Viewing permissions

Use the ls command’s -l option to view the permissions (or file mode) set for the contents of a directory, for example:

The first column is what we must focus on. Taking an example value of drwxrwxrwx+ , the meaning of each character is explained in the following tables:

| d | rwx | rwx | rwx | + |

| The file type, technically not part of its permissions. See info ls -n «What information is listed» for an explanation of the possible values. | The permissions that the owner has over the file, explained below. | The permissions that the group has over the file, explained below. | The permissions that all the other users have over the file, explained below. | A single character that specifies whether an alternate access method applies to the file. When this character is a space, there is no alternate access method. A . character indicates a file with a security context, but no other alternate access method. A file with any other combination of alternate access methods is marked with a + character, for example in the case of Access Control Lists. |

Each of the three permission triads ( rwx in the example above) can be made up of the following characters:

| Character | Effect on files | Effect on directories | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Read permission (first character) | — | The file cannot be read. | The directory’s contents cannot be shown. |

| r | The file can be read. | The directory’s contents can be shown. | |

| Write permission (second character) | — | The file cannot be modified. | The directory’s contents cannot be modified. |

| w | The file can be modified. | The directory’s contents can be modified (create new files or directories; rename or delete existing files or directories); requires the execute permission to be also set, otherwise this permission has no effect. | |

| Execute permission (third character) | — | The file cannot be executed. | The directory cannot be accessed with cd. |

| x | The file can be executed. | The directory can be accessed with cd; this is the only permission bit that in practice can be considered to be «inherited» from the ancestor directories, in fact if any directory in the path does not have the x bit set, the final file or directory cannot be accessed either, regardless of its permissions; see path_resolution(7) for more information. | |

| s | The setuid bit when found in the user triad; the setgid bit when found in the group triad; it is not found in the others triad; it also implies that x is set. | ||

| S | Same as s , but x is not set; rare on regular files, and useless on directories. | ||

| t | The sticky bit; it can only be found in the others triad; it also implies that x is set. | ||

| T | Same as t , but x is not set; rare on regular files. | ||

See info Coreutils -n «Mode Structure» and chmod(1) for more details.

Examples

Let us see some examples to clarify:

Archie has full access to the Documents directory. They can list, create files and rename, delete any file in Documents, regardless of file permissions. Their ability to access a file depends on the file’s permissions.

Archie has full access except they can not create, rename, delete any file. They can list the files and (if the file’s permissions allow it) may access an existing file in Documents.

Archie can not do ls in the Documents directory but if they know the name of an existing file then they may list, rename, delete or (if the file’s permissions allow it) access it. Also, they are able to create new files.

Archie is only capable of (if the file’s permissions allow it) accessing those files the Documents directory which they know of. They can not list already existing files or create, rename, delete any of them.

You should keep in mind that we elaborate on directory permissions and it has nothing to do with the individual file permissions. When you create a new file it is the directory that changes. That is why you need write permission to the directory.

Let us look at another example, this time of a file, not a directory:

Here we can see the first letter is not d but — . So we know it is a file, not a directory. Next the owner’s permissions are rw- so the owner has the ability to read and write but not execute. This may seem odd that the owner does not have all three permissions, but the x permission is not needed as it is a text/data file, to be read by a text editor such as Gedit, EMACS, or software like R, and not an executable in its own right (if it contained something like python programming code then it very well could be). The group’s permissions are set to r— , so the group has the ability to read the file but not write/edit it in any way — it is essentially like setting something to read-only. We can see that the same permissions apply to everyone else as well.

Changing permissions

chmod is a command in Linux and other Unix-like operating systems that allows to change the permissions (or access mode) of a file or directory.

Text method

To change the permissions — or access mode — of a file, use the chmod command in a terminal. Below is the command’s general structure:

Where who is any from a range of letters, each signifying who is being given the permission. They are as follows:

- u : the user that owns the file.

- g : the user group that the file belongs to.

- o : the other users, i.e. everyone else.

- a : all of the above; use this instead of typing ugo .

The permissions are the same as discussed in #Viewing permissions ( r , w and x ).

Now have a look at some examples using this command. Suppose you became very protective of the Documents directory and wanted to deny everybody but yourself, permissions to read, write, and execute (or in this case search/look) in it:

Before: drwxr-xr-x 6 archie web 4096 Jul 5 17:37 Documents

After: drwx—— 6 archie web 4096 Jul 6 17:32 Documents

Here, because you want to deny permissions, you do not put any letters after the = where permissions would be entered. Now you can see that only the owner’s permissions are rwx and all other permissions are — .

This can be reverted with:

Before: drwx—— 6 archie web 4096 Jul 6 17:32 Documents

After: drwxr-xr-x 6 archie web 4096 Jul 6 17:32 Documents

In the next example, you want to grant read and execute permissions to the group, and other users, so you put the letters for the permissions ( r and x ) after the = , with no spaces.

You can simplify this to put more than one who letter in the same command, e.g:

Now let us consider a second example, suppose you want to change a foobar file so that you have read and write permissions, and fellow users in the group web who may be colleagues working on foobar , can also read and write to it, but other users can only read it:

Before: -rw-r—r— 1 archie web 5120 Jun 27 08:28 foobar

After: -rw-rw-r— 1 archie web 5120 Jun 27 08:28 foobar

This is exactly like the first example, but with a file, not a directory, and you grant write permission (just so as to give an example of granting every permission).

Text method shortcuts

The chmod command lets add and subtract permissions from an existing set using + or — instead of = . This is different from the above commands, which essentially re-write the permissions (e.g. to change a permission from r— to rw- , you still need to include r as well as w after the = in the chmod command invocation. If you missed out r , it would take away the r permission as they are being re-written with the = . Using + and — avoids this by adding or taking away from the current set of permissions).

Let us try this + and — method with the previous example of adding write permissions to the group:

Before: -rw-r—r— 1 archie web 5120 Jun 27 08:28 foobar

After: -rw-rw-r— 1 archie web 5120 Jun 27 08:28 foobar

Another example, denying write permissions to all (a):

Before: -rw-rw-r— 1 archie web 5120 Jun 27 08:28 foobar

After: -r—r—r— 1 archie web 5120 Jun 27 08:28 foobar

A different shortcut is the special X mode: this is not an actual file mode, but it is often used in conjunction with the -R option to set the executable bit only for directories, and leave it unchanged for regular files, for example:

Copying permissions

It is possible to tell chmod to copy the permissions from one class, say the owner, and give those same permissions to group or even all. To do this, instead of putting r , w , or x after the = , put another who letter. e.g:

Before: -rw-r—r— 1 archie web 5120 Jun 27 08:28 foobar

After: -rw-rw-r— 1 archie web 5120 Jun 27 08:28 foobar

This command essentially translates to «change the permissions of group ( g= ), to be the same as the owning user ( =u ). Note that you cannot copy a set of permissions as well as grant new ones e.g.:

In that case chmod throw an error.

Numeric method

chmod can also set permissions using numbers.

Using numbers is another method which allows you to edit the permissions for all three owner, group, and others at the same time, as well as the setuid, setgid, and sticky bits. This basic structure of the code is this:

Where xxx is a 3-digit number where each digit can be anything from 0 to 7. The first digit applies to permissions for owner, the second digit applies to permissions for group, and the third digit applies to permissions for all others.

In this number notation, the values r , w , and x have their own number value:

To come up with a 3-digit number you need to consider what permissions you want owner, group, and all others to have, and then total their values up. For example, if you want to grant the owner of a directory read write and execution permissions, and you want group and everyone else to have just read and execute permissions, you would come up with the numerical values like so:

This is the equivalent of using the following:

To view the existing permissions of a file or directory in numeric form, use the stat(1) command:

Where the %a option specifies output in numeric form.

Most directories are set to 755 to allow reading, writing and execution to the owner, but deny writing to everyone else, and files are normally 644 to allow reading and writing for the owner but just reading for everyone else; refer to the last note on the lack of x permissions with non executable files: it is the same thing here.

To see this in action with examples consider the previous example that has been used but with this numerical method applied instead:

Before: -rw-r—r— 1 archie web 5120 Jun 27 08:28 foobar

After: -rw-rw-r— 1 archie web 5120 Jun 27 08:28 foobar

If this were an executable the number would be 774 if you wanted to grant executable permission to the owner and group. Alternatively if you wanted everyone to only have read permission the number would be 444 . Treating r as 4, w as 2, and x as 1 is probably the easiest way to work out the numerical values for using chmod xxx filename , but there is also a binary method, where each permission has a binary number, and then that is in turn converted to a number. It is a bit more convoluted, but here included for completeness.

Consider this permission set:

If you put a 1 under each permission granted, and a 0 for every one not granted, the result would be something like this:

You can then convert these binary numbers:

The value of the above would therefore be 775.

Consider we wanted to remove the writable permission from group:

The value would therefore be 755 and you would use chmod 755 filename to remove the writable permission. You will notice you get the same three digit number no matter which method you use. Whether you use text or numbers will depend on personal preference and typing speed. When you want to restore a directory or file to default permissions e.g. read and write (and execute) permission to the owner but deny write permission to everyone else, it may be faster to use chmod 755/644 filename . However if you are changing the permissions to something out of the norm, it may be simpler and quicker to use the text method as opposed to trying to convert it to numbers, which may lead to a mistake. It could be argued that there is not any real significant difference in the speed of either method for a user that only needs to use chmod on occasion.

You can also use the numeric method to set the setuid , setgid , and sticky bits by using four digits.

For example, chmod 2777 filename will set read/write/executable bits for everyone and also enable the setgid bit.

Bulk chmod

Generally directories and files should not have the same permissions. If it is necessary to bulk modify a directory tree, use find to selectively modify one or the other.

To chmod only directories to 755:

To chmod only files to 644:

Changing ownership

chown changes the owner of a file or directory, which is quicker and easier than altering the permissions in some cases.

Consider the following example, making a new partition with GParted for backup data. Gparted does this all as root so everything belongs to root by default. This is all well and good but when it comes to writing data to the mounted partition, permission is denied for regular users.

As you can see the device in /dev is owned by root, as is the mount location ( /media/Backup ). To change the owner of the mount location one can do the following:

Before: drwxr-xr-x 5 root root 4096 Jul 6 16:01 Backup

After: drwxr-xr-x 5 archie root 4096 Jul 6 16:01 Backup

Now the partition can have data written to it by the new owner, archie, without altering the permissions (as the owner triad already had rwx permissions).

Access Control Lists

Access Control Lists provides an additional, more flexible permission mechanism for file systems by allowing to set permissions for any user or group to any file.

Umask

The umask utility is used to control the file-creation mode mask, which determines the initial value of file permission bits for newly created files.

File attributes

Apart from the file mode bits that control user and group read, write and execute permissions, several file systems support file attributes that enable further customization of allowable file operations.

The e2fsprogs package contains the programs lsattr(1) and chattr(1) that list and change a file’s attributes, respectively.

These are a few useful attributes. Not all filesystems support every attribute.

- a — append only: File can only be opened for appending.

- c — compressed: Enable filesystem-level compression for the file.

- i — immutable: Cannot be modified, deleted, renamed, linked to. Can only be set by root.

- j — data journaling: Use the journal for file data writes as well as metadata.

- m — no compression: Disable filesystem-level compression for the file.

- A — no atime update: The file’s atime will not be modified.

- C — no copy on write: Disable copy-on-write, for filesystems that support it.

See chattr(1) for a complete list of attributes and for more info on what each attribute does.

For example, if you want to set the immutable bit on some file, use the following command:

To remove an attribute on a file just change + to — .

Extended attributes

From xattr(7) : «Extended attributes are name:value pairs associated permanently with files and directories». There are four extended attribute classes: security, system, trusted and user.

Extended attributes are also used to set Capabilities.

User extended attributes

User extended attributes can be used to store arbitrary information about a file. To create one:

Use getfattr to display extended attributes:

Finally, to remove an extended attribute:

Preserving extended attributes

| Command | Required flag |

|---|---|

| cp | —preserve=mode,ownership,timestamps,xattr |

| mv | preserves by default 1 |

| tar | —xattrs for creation and —xattrs-include=’*’ for extraction |

| bsdtar | -p for extraction |

| rsync | —xattrs |

- mv silently discards extended attributes when the target file system does not support them.

To preserve extended attributes with text editors you need to configure them to truncate files on saving instead of using rename(2) .[1]

Tips and tricks

Preserve root

Use the —preserve-root flag to prevent chmod from acting recursively on / . This can, for example, prevent one from removing the executable bit systemwide and thus breaking the system. To use this flag every time, set it within an alias. See also [2].